Artist Interview: Yermo Aranda

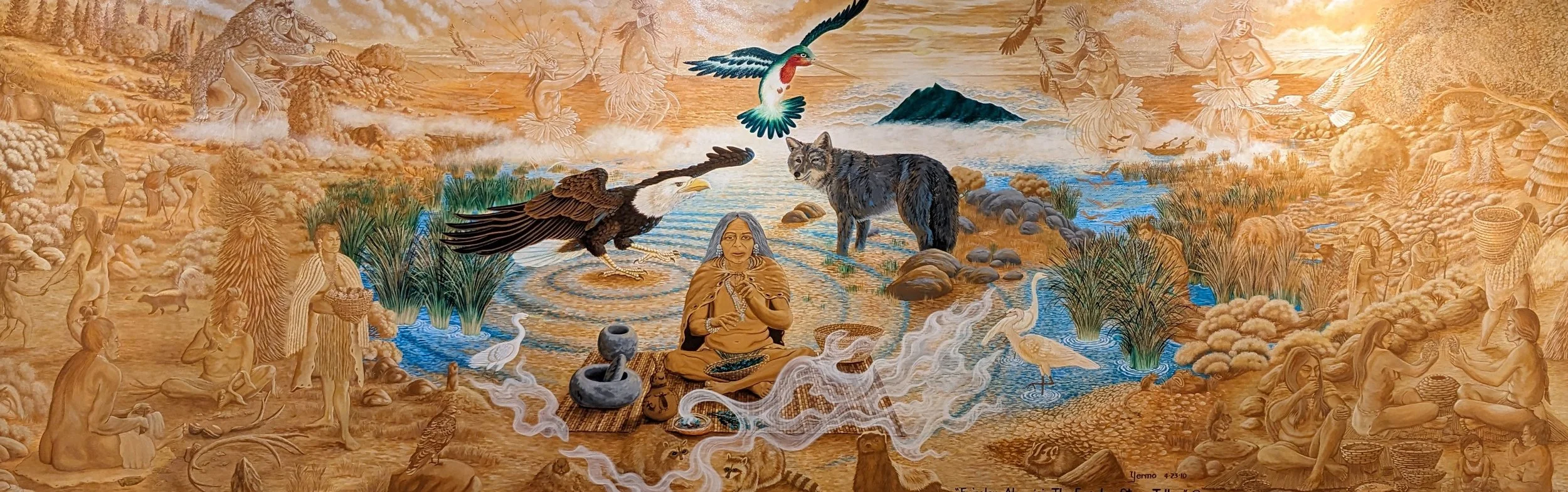

Yermo Aranda “The Esselen Story Teller” - on display in the Santa Cruz Art League gallery through February 20

Guillermo Aranda—known to most as Yermo—has been creating art for more than half a century, guided by instinct, culture, and an unwavering commitment to community. The name “Yermo,” a childhood nickname that stuck, has become his artistic signature—something like a brand or trademark, he says with a smile.

Primarily known as a muralist, Yermo first became involved in mural work in 1969. But to call him only a muralist would be limiting. “I really just love creating anything,” he explains. Over the years, his artistic practice has included pottery, silversmithing, jewelry-making, drum-making, leatherwork, and more. Still, painting remains at the core of his work. After a lifetime of experimentation, he found himself returning again and again to acrylics. “My mind is constantly moving,” he says. “Acrylics can keep up with me.”

Yermo’s relationship with art began early. He traces the moment he realized he was an artist back to the fourth grade. Assigned to draw storybook characters, he chose Paul Bunyan and the Big Blue Ox. Days later, he walked into school and saw his drawing displayed with a blue ribbon. “I knew what that ribbon meant,” he recalls. “I just stood there and looked at it. I couldn’t get over it.”

Creativity ran deep in his family. His father was a painter and musician, his uncles artists and craftspeople—one even built violins in a basement workshop. While they tried to guide him toward music, it never quite clicked. “I didn’t have the ear for it,” he admits.

But when they saw him drawing, they shifted gears, surrounding him with pencils, paper, and books. That encouragement carried him through high school and beyond.

After high school, Yermo served in the military as a jet engine mechanic and initially planned to pursue a career in mechanics. But while attending classes to advance his license, he found himself lingering outside art classrooms, drawn in. “That’s when I decided to change my major,” he says. “Everything always leads me back to art,” especially art rooted in culture and tradition.

One of the most formative works of his career is The Esselen Story Teller, created as his capstone project and completed in 2010. The piece was exhibited at CSU Monterey Bay’s student center for over a decade before being dismantled and placed in storage. Though the physical work has been out of sight, its influence has never faded. “Since then, I’ve continued to include elements of the original people of this area,” Yermo explains. “I always try to acknowledge the original people in my murals. That research is still coming out in my work, even today.”

When asked what he hopes viewers take away from his art, his answer is immediate: pride. “Pride in knowing that we have history and culture that we can be proud of,” he says. But that pride, he notes, requires effort. “You have to go searching for it, because it’s not made available to you.”

Growing up in San Diego, Yermo experienced racism firsthand—living “on the other side of the tracks,” navigating policing and exclusion, and later encountering similar dynamics during military service. These experiences shaped not only his worldview, but his artistic purpose. “There was a point where I had to decide if anger was going to be

my motivation, or love and dignity,” he reflects. “That’s why I paint—to give people a sense of dignity and pride in who we are.”

The current exhibit at SCAL reflects more than 50 years of that commitment. The collection includes drawings dating back to the 1970s, along with works connected to mural projects across decades. The exhibit includes work from Yermo’s role in the founding of the murals at Chicano Park in San Diego. In the 1970s, he served as lead artist during the initiation of what would become one of the most significant public art sites in the world. Today, nearly 100 murals cover the pillars of the Coronado Bay Bridge, and the park is recognized at the city, state, and federal levels as a historic site.

“People know about it around the world,” Yermo says. “And I was a part of that.”

For the opening reception, dancers will perform, and the space will be ceremonially saged—an act of respect and intention. “I’m excited,” he says simply. After a lifetime of creating, teaching, and honoring culture through art, it’s clear that Yermo’s work is not just about what’s on the wall, but about history, community, and the stories that deserve to be seen.

Interview by Gavin Kennedy